Exploring the Boundary Conditions of the Effect of Aesthetics on Perceived Usability (2018)

Motivation

Doctoral Dissertation_North Carolina State University

[The following description is a summary of my doctoral dissertation. Click here for a full printable version (.pdf).]

Abstract

This research examined whether users’ judgments of usability and aesthetics, as well as any association between the two, might change with their continued experience with a system. The study explored the hypotheses that 1) aesthetics contribute disproportionately to judgments of usability, and that 2) the influence of aesthetics on judgments of usability will diminish with continued use and experience.

We developed four versions of a prototype website, a patient portal for a fictitious medical practice. We manipulated two variables, usability and aesthetics, to produce the four versions: High Aesthetics High Usability, High Aesthetics Low Usability, Low Aesthetics High Usability, Low Aesthetics Low Usability. Participants were recruited to perform three online tasks on each of the four versions of the website. After each task, users’ perceptions of usability (SUS) and aesthetics (Lavie and Tractinsky’s (2004) classical and expressive instrument, Moshagen and Thielsch’s (2010, 2013) VisAWI-S tool) were gauged and performance measures were recorded.

Results provided very limited support for the hypotheses. The hypotheses proposed that, at observation 1, aesthetics would contribute disproportionately to judgments of usability, and that the influence of aesthetics on judgments of usability would diminish with repeated use. Though Pearson correlations showed some degree of association between ratings of usability and aesthetics, repeated measures ANOVAs failed to show an effect of aesthetics on users’ judgments of usability. Indeed, results suggested that SUS ratings were unaffected by aesthetics. Instead, the analyses showed a significant effect of occasion and usability, rather than aesthetics, on users’ judgments of usability. Some past studies have found that users' experience with the usability of a system affected their judgments of the aesthetics of the system (i.e., "what is usable is beautiful"), but the current study suggests that users' assessments of the aesthetics of a website are unrelated to the website's usability.

Procedure

The main elements of the study were: (1) development of the website/patient portal, (1a) confirmation of the manipulation of aesthetics, (1b) confirmation of the manipulation of usability, and (2) assessing the relation between aesthetics and usability

1) Development of the website/patient portal

We created four versions of a patient portal website: High Aesthetics High Usability, High Aesthetics Low Usability, Low Aesthetics High Usability, Low Aesthetics Low Usability.

1a) Confirmation of the manipulation of aesthetics

To confirm that our manipulation of aesthetics factors had indeed produced the desired difference in perceived aesthetics between the high (HAHU, HALU) and low (LAHU, LALU) aesthetics versions of the websites, we used the survey software Qualtrics to create a survey that presented three images from each of the four versions of the website. The images were screenshots of the actual websites. One representative image from each of the three tasks was chosen from each of the four versions of the website for a total of twelve images (1 image per task x 3 tasks per website x 4 versions of the website = 12 images). Additionally, a practice block of three images was created so that participants could become familiar with the procedure and format of the experiment. The practice block contained three images that were unrelated to the websites and bore no resemblance to screenshots from them.

Home page of

High Aesthetics High Usability

version of the website

Home page of

High Aesthetics Low Usability

version of the website

Home page of

Low Aesthetics High Usability

version of the website

Home page of

Low Aesthetics Low Usability

version of the website

Participants—We recruited 50 online research participants through the Internet-based recruiting site Amazon Mechanical Turk.

Procedure—Participants viewed the practice block of three images. The images were presented in random order for five seconds per image. After the presentation of the three-image practice block, participants answered five questions asking them to rate the attractiveness of the images on a scale of 0 to 10, with 0 meaning not at all attractive and 10 meaning extremely attractive. Participants then viewed the twelve images of the websites presented in blocks of three for each version of the website. The blocks were presented in random order. After viewing each three-image block, participants were asked the same set of questions that they had answered after the practice block. Participants answered the questions and were then shown the next block of three images, presented in random order, and the process was repeated until participants had rated the aesthetics of the images from all four websites.

Results—Matched samples t-Tests comparing the ratings of the images from the high aesthetics (HAHU, HALU) and low aesthetics (LAHU, LALU) versions of the website indicated that, on all five questions, users judged the high aesthetics versions to be more attractive than the low aesthetics versions.

1b) Confirmation of the manipulation of usability

To confirm that our manipulations of usability factors produced the desired differences in perceived usability, we used the online, remote usability testing tool, Loop11, to create an online usability test of all four versions of the patient portal/website.

Participants—We recruited 40 online research participants for each version of the website using the online labor system Amazon Mechanical Turk.

Procedure—Participants performed three tasks on the website version to which they were assigned. For example, participants who were assigned to the LALU version of the website performed three tasks on that version, and that version only. Those assigned to the HAHU, HALU, and LAHU versions performed the three tasks on those versions. The three tasks were:

- Find non-fasting glucose level for patient Jane Doe

- Find how much patient Jane Doe owes

- Schedule an appointment for patient Jane Doe

After completing the three tasks, participants were asked the following questions:

- How usable was the website on which you just performed the task?

- How difficult to use was the website on which you just performed the task?

- How user friendly was the website on which you just performed the task?

Participants were asked to answer the three questions on a 1-10 scale, with 1 meaning low and 10 meaning high.

Results—Users judged the high usability versions (HAHU, LAHU) of the website more usable, more user friendly, and less difficult to use than the low usability versions (HALU, LALU). The mean ratings for the three questions are summarized in Table 4 in the full version of this dissertation. The ratings were also compared using independent samples t-Tests. The t-Tests confirmed that users’ perceptions of the usability of the websites were significantly higher for the high usability versions than for the low usability versions.

2) Assessing the relation between aesthetics and usability

For this portion of the study, we again used the online, remote usability testing tool, Loop11, to create an online usability test of all four versions of the patient portal/website. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the four versions of the website/patient portal. On four consecutive days, participants performed three tasks on the version of the website to which they were assigned. After each task, participants rated the website on measures of usability and aesthetics.

Measure of usability. Because of its widespread use and acceptance as a measure of usability (Brooke, 1996), this study employed the SUS (Appendix 1 in the full version of this dissertation) as the principle measure of usability. Participants were asked to perform three tasks on the website/patient portal, and to complete the SUS after each task.

Measure of aesthetics. This study employed the classical and expressive instrument developed by Lavie and Tractinsky (Lavie and Tractinsky, 2003) and the short version of the Visual Aesthetics of Website Inventory (VisAWI-S) tool developed by Moshagen and Thielsch (Moshagen and Thielsch, 2010, 2013). These instruments are provided in Appendices 2 and 3 in the full version of this dissertation.

Tasks. Participants performed three tasks on the website/patient portal on four successive days/occasions/observations. The three tasks were ecologically valid in that they were representative of typical tasks that patients might perform on patient portals of real-world medical practices. The three tasks were:

- Find non-fasting glucose level

- Determine what amount, if any, that patient still owed

- Schedule an appointment

Participants—We collected data from approximately 30 users per website version (HAHU, etc.), conducted in two rounds, using the online labor system Amazon Mechanical Turk.

Procedure—Participants performed the three tasks on the website/patient portal. After completion of the tasks, in addition to completing the SUS, participants completed Lavie and Tractinsky’s classical (CA) and expressive (CE) instruments, as well as the short version of Moshagen and Thielsch’s VisAWI-S tool. To measure changes in perceived usability and aesthetics over time, the same groups of participants performed the three tasks on the same version of the patient portal on four successive days/occasions/observations, completing the measurements of usability and aesthetics after each task on all four occasions.

Results—Users' perceptions of usability increased over the four observations, but their perceptions of aesthetics did not.

SUS

High Aesthetics High Usability

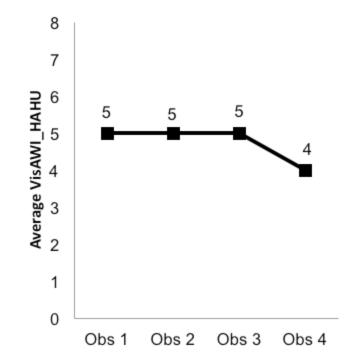

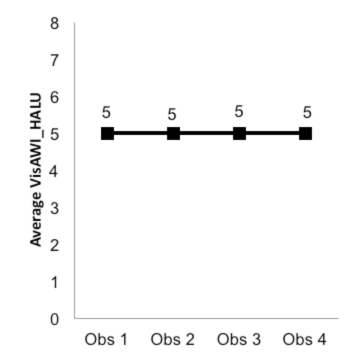

Aesthetics (VisAWI)

High Aesthetics High Usability

SUS

High Aesthetics Low Usability

Aesthetics (VisAWI)

High Aesthetics Low Usability

SUS

Low Aesthetics High Usability

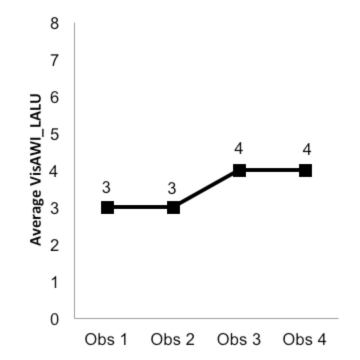

Aesthetics (VisAWI)

Low Aesthetics High Usability

SUS

Low Aesthetics Low Usability

Aesthetics (VisAWI)

Low Aesthetics Low Usability

Additionally, RMANOVAs (below) showed a main effect of the manipulation of interface usability on users’ perceptions of usability as reflected in SUS scores, as well as a main effect of aesthetics on users’ perceptions of aesthetics as reflected in VisAWI and CA ratings. The absence of main effects of the interface aesthetics manipulation on SUS ratings or of the interface usability manipulation on VisAWI, CA, or CE ratings suggest that usability and aesthetics were perceived separately in this experiment.

Likewise, the failure to observe an interaction between the usability manipulation and the aesthetics manipulation for the SUS, VisAWI, CA, or CE measures indicates the lack of a joint effect on perceptions of usability or aesthetics. Finally, the significant effect of occasion on SUS ratings, but not on VisAWI, CA, or CE shows that repeated experience affected usability perception but not aesthetic perception.

Results of 2 (Aesthetics: Low, High) X 2 (Usability: Low, High) X 4 (Occasion: Observations 1, 2, 3 and 4 ofoverall SUS scores, averaged across the three tasks) repeated measures ANOVA showing a significant effect of occasion and usability, but no interaction of occasion with aesthetics or usability.

Results of 2 (Aesthetics: Low, High) X 2 (Usability: Low, High) X 4 (Occasion: Observations 1, 2, 3 and 4 ofoverall CA scores, averaged across the three tasks) repeated measures ANOVA showing a significant effect of aesthetics, but no effect of occasion and no interaction of occasion with aesthetics or usability.

Results of 2 (Aesthetics: Low, High) X 2 (Usability: Low, High) X 4 (Occasion: Observations 1, 2, 3 and 4 ofoverall VisAWI scores, averaged across the three tasks) repeated measures ANOVA showing a significant effect of aesthetics, but no effect of occasion and no interaction of occasion with aesthetics or usability.

Results of 2 (Aesthetics: Low, High) X 2 (Usability: Low, High) X 4 (Occasion: Observations 1, 2, 3 and 4 ofoverall CE scores, averaged across the three tasks) repeated measures ANOVA showing no significant effect of aesthetics, no effect of occasion, and no interaction of occasion with aesthetics or usability.

Discussion—Based largely on previous studies, the authors of this study hypothesized that aesthetics might contribute disproportionately to judgments of usability in early interactions with websites, and that with continued use, the role of aesthetics would diminish with respect to overall perception of usability. The results found here provided very limited support for these hypotheses. Repeated measures ANOVAs failed to show an effect of aesthetics on users’ judgments of usability. In fact, results suggested that SUS ratings were unaffected by aesthetics. ANOVAs also showed a significant effect of observation and usability, rather than aesthetics, on users’ judgments of usability.

In some of the research that preceded this study, results were purely correlational and this study replicated some of those purely correlational results. However, it is possible that the significant correlations between users’ ratings of aesthetics and usability in this and previous studies were produced by an effect of scale use by participants, rather than by a relationship between aesthetics and usability.

In a 2012 study, Tuch, Roth, Hornbaek, Opwis, and Bargas-Avila’s found that, under certain circumstances, the effect of interface usability on classical aesthetics and hedonic quality stimulation was affected by the users’ affective experience with the usability of the website. Users who were frustrated by the interface’s low usability lowered their aesthetics ratings. In other words, users’ poor performance tended to lower their assessments of the websites aesthetics. Tuch et al. summarized this finding thusly, “Our results show that Tractinsky’s notion (“what is beautiful is usable”) can be reversed to a “what is usable is beautiful” effect under certain circumstances” (p. 1604). By contrast, the current study found that users’ affective experience with the usability of the website affected not their assessments of the aesthetics of the website, but of the usability instead. Thus, whereas Tuch et al. (2012) summarized their findings as “what is usable is beautiful” under certain circumstances, the findings of the current study could be summarized as “what is usable is whatever makes me feel successful” under certain circumstances.